Inspired from making balsamic vinegar and reading Tai’s food explorations on Currents, my first step toward expanding my fermentation resume starts with tempeh. Originally from Indonesia, tempeh is made of whole soybeans fermented with a fungus to form a whitish cake. In the West, it’s known as a vegetarian meat substitute high in fiber and protein. Although superficially similar to tofu, tempeh has a firmer texture (even when compared to extra-firm tofu) and a nutty, even earthy taste.

Making tempeh only requires 3 ingredients: dry soybeans, rice vinegar, and tempeh starter (i.e. the fungal spores). To begin, I soaked the dry soybeans overnight to prepare them for cooking the next day. Using a pressure cooker certainly speeds things up, and I reckon the overnight soaking step is unnecessary as it seems that the key is having fully-cooked beans. I’ve read different types of beans can be used as the base to replace soybeans to make a soy-free alternative. However, keep in mind if you do use black beans or chickpeas instead, the resulting tempeh will certainly not be as high in protein, and the taste will probably be different. Tempeh is traditionally made from the soy solids from the production of soy milk, called soy pulp, which are otherwise used as fodder and compost. This is a future project I’d like to try out.

The soybeans should be left to dry and cool down to room temperature. Some places say to remove hulls, but I personally did not find this to be necessary or desirable as the hulls are nutritious with fiber and some protein. I then mixed the cooked soybeans, rice vinegar, and starter together at the following ratio:

1 cup cooked beans - 1 tablespoon rice vinegar - 1/4 teaspoon tempeh starter

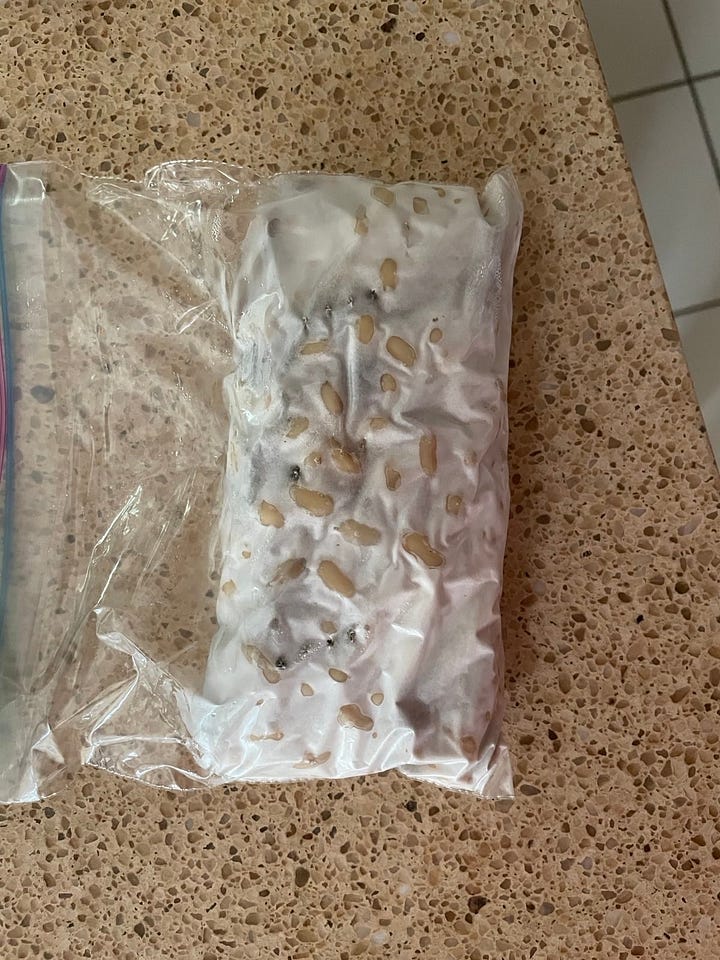

The vinegar serves to create an acidic environment for the fungus that prevents unwanted bacterial growth. I used Japanese mirin, but I don’t see why apple cider vinegar couldn’t be used as an alternative. I put the beans into plastic bags and molded them into tempeh-shaped cakes (blocks roughly 1 x 3 x 7″ in size); traditionally, tempeh is wrapped in banana leaves to ferment. I made small holes into the plastic bags to help with air circulation, though I’m doubtful as to how much this impacted the final product. In the future, I’d also like to experiment with making tempeh from reusable containers to limit my use of single-use plastics.

Next is the waiting game. The bags of beans should be placed somewhere between 85-90F for 24-48 hours. The temperature is key for the spores to develop properly; my first attempt failed because temperatures were north of 100 degrees. This time, I put them in the oven with the light on which sat at a perfect 87F. Next time I make tempeh, I’d like to take advantage of the East Coast’s hot and humid summers and ferment the tempeh outside - recent temperatures in DC have been roughly similar to those in Jakarta, so I think it could work.

After 36 hours, the white fungus completely envelopped the soybeans. After 48 hours, they were ready to eat. You know when your tempeh is ready when it’s completely white (black specks are fine, but any other colours probably indicate contamination) and feels firm and solid. To taste test my creation, I fried slices of tempeh in a pan. Tempeh can be cooked much like tofu, though its texture encourages grilling, frying, and baking. Compared to the store-bought variety, my homemade tempeh was not as dense (which may be due to the lack of fillers like rice flour), but had a stronger, nuttier taste.

Amid my feelings of self-accomplishment and satisfaction while eating the tempeh, I had a cultural realization. While rice is inextricably tied to Asian, and by that I mean East and Southeast Asian, cuisine, I would argue that the true defining crop of Asian food culture is the soybean. While many other cultures eat rice (e.g. Persian tahdig, Jamaican rice and beans, Italian risotto), the world owes its many permutations of the soybean to the handful of cultures that make up East and Southeast Asia. There’s soy sauce, soy milk, tofu, edamame, miso, natto, oncom, soy protein, Chinese chili bean paste, and, of course, tempeh. While rice may be substituted with wheat noodles, you’d be hard pressed to find an Asian dish without soy. Rice may be synonymous with food, but the uniqueness of Asian cuisine is defined by the soybean.

Edit (Jul 21, 2021): Making tempeh in reusable containers could work in theory, but I found that the soybeans cannot be as tightly packed together, resulting in less appetizing tempeh. However, I thought the tempeh I made with soy pulp was very tasty, almost like a chicken nugget in texture. I could see it being a good meat replacement if one were to add the right flavourings. I do wonder how the nutritional content compares to whole soybean tempeh though. Another conclusion I had with later editions of my homemade tempeh is that it is particularly suited for the air fryer because, in a pan, tempeh tends to soak up a lot of oil.