I’ve had a deep obsession with yetis from a young age. After seeing my first yeti in the Y section of an encyclopedia at the age of six or so, I developed a strong fear that one would try to kidnap me if I was alone. Yet, despite my fear, I maintained a deep curiosity for yetis which continues today (fortunately, my yeti phobia has since waned). In this post, I’ll explore the culture behind the infamous ape that plagued my childhood.

Origins

The yeti, also called the abominable snowman, is a cryptid said to inhabit Himalayan regions. It’s most commonly described as an ape-like creature, which often draws comparisons to Bigfoot of North America.

The English word yeti originates from the Sherpa word for “cliff bear” ( གཡའ་དྲེད).1 Among Himalayan cultures, there are at least two types of yeti: the “cattle bear” (ཕྱུགས་དྲེད) and the “man-bear” (མི་དྲེད). The cattle bear is largely recognized to be the Himalayan brown bear. The man-bear is what us Westerners call the yeti and despite its name, Himalayan peoples distinguish it from recognized bear species. In contrast to their common depictions, yetis are believed to live in the high altitude alpine forests rather than snow-capped Himalayan mountaintops.

There are many theories on what the yeti could be zoologically. Bears, which often stand on their hind legs, are the main culprit. In Himalayan regions, there are the Tibetan blue bear (Ursus arctos pruinosus) and the Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus), which are both subspecies of brown bear. However, the yeti is specifically described as having a short snout like a monkey or human.

Another suspect for yeti misidentification are monkeys. Nepal grey langurs (Semnopithecus schistaceus) and golden snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) are both large monkeys that live in Himalayan mountain forests. While these species are large for monkeys, they don’t attain the size of yetis. Furthermore, they are primarily arboreal, so it would be unlikely to see them standing on the ground.

More out there theories suggest that the yeti is an extant species of Gigantopithecus or hominid. Gigantopithecus blacki was a large, extinct species of ape that lived in prehistoric China. Although its identified fossils are only tooth and jaw remains, Gigantopithecus is thought to be the largest primate ever recorded. Its closest living relative is the orangutan, which means they probably did not walk upright like the yeti. Owing to its connotations as a wild man, other cryptozoologists think the yeti could be a Neanderthal or some other human relative.

The Yeti in Himalayan Cultures

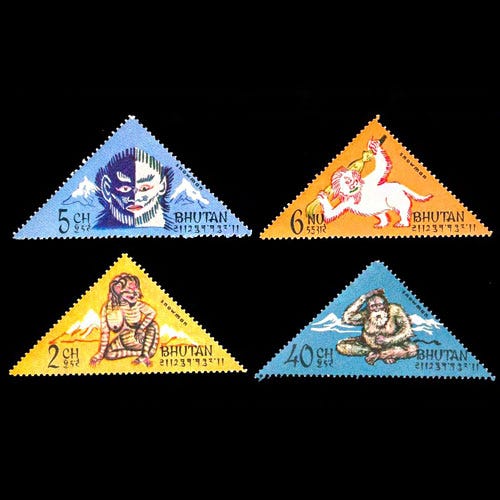

The yeti has been a fascination in the West since the 1920s, but its depiction in Himalayan cultures is much older. The Tibetan creation myth describes the origin of the Tibetan people from a mythical monkey (ཕ་སྤྲེལ་རྒན་བྱང་ཆུབ་སེམས་པ), an emanation of Avalokiteshvara, and a rock demoness (བྲག་སྲིན་མོ), an emanation of Tara. Their children became the six original Tibetan clans, but some of the ancestors of the Tibetan people retained their simian traits and became yetis. Thus, yetis occupy the liminal space between human and animal in Himalayan cultures.

Owing to their part human nature, yetis are said to be human enough to practice Buddhism. Famously, Pangboche Monastery in Nepal housed a yeti scalp and hand. Though they were found to be human after DNA analysis, these artifacts are said to be the remains of a yeti disciple of Lama Sangwa Dorje (གསང་བ་རྡོ་རྗེ), who took care of the lama while he was on a spiritual retreat.

Female yetis are depicted as buxom, and it’s apparently a notable physical characteristic of theirs. Interestingly, the same thing is said about Bigfoot in North America. The Bigfoot of the infamous Patterson-Gimlin film is identified as a “she” from her prominent breasts. In fact, this is often brought forward as evidence for the authenticity of the Bigfoot sighting—after all, why would a gorilla suit have boobs?

Some say that yetis are magical. Yetis hold a wand of invisibility (སྒྲིབ་ཤིང) that grants them invisibility at will. It’s apparently possible for humans to acquire this magic wand.

First, one must find a magpie’s nest and steal one of its eggs. Then, that egg must be hard-boiled and returned to the nest. The mother magpie, frustrated that her lone egg won’t hatch, will go in search for the yeti’s wand. This wand looks no different than an ordinary twig and is found under a yeti’s right arm. Once found, the hard-boiled egg will hatch due to the magic of the wand. After the birds have left the nest, one can take the magpie nest and put it in a stream or river. Normally, the sticks of the nest will flow downstream from the water’s current. But, within that bundle, there will be one twig that flows in the reverse—that is the yeti’s magic wand.

In Tibetan, the yeti also goes by several other names including “wild man” (མི་རྒོད), “snow man” (གངས་མི), and simply “big man” (མི་ཆེན་པོ).